| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

https://thefilmstage.com/nostalghia-cinematographer-giuseppe-lanci-on-andrei-tarkovskys-total-control-and-overseeing-the-new-restoration/

Nostalghia Cinematographer Giuseppe Lanci on Andrei Tarkovsky's Total Control and Overseeing the New Restoration

In Andrei Tarkovsky's penultimate film Nostalghia (1983), which he co-wrote with Michelangelo Antonioni's longtime collaborator Tonino Guerra, Russian writer Andrei (Oleg Ivanovič Jankovskij) travels to Italy in order to research the life of composer Pavel Sosnovsky, along with his interpreter Eugenia (Domiziana Giordano), a young woman who resembles the Madonna del Parto in the famous fresco by Piero della Francesca.

Ahead of the theatrical release of the new 4K restoration, now playing at NYC's Film Forum, we had the opportunity to speak with Giuseppe Lanci, the Italian cinematographer who shot the film and oversaw this new restoration. The 81-year-old Lanci still teaches at the CSC (National School of Cinema of Rome). In his diaries, Tarkovsky mentioned watching Nostalghia with cinematographer Sven Nykvist: "The photography made a strong impression on Nykvist. Indeed, Peppe Lanci shot the film in an extraordinary manner. This Swedish copy is much better than the one shown at Cannes, which was our working copy."

The Film Stage: Can you talk about the new 4K restoration of Nostalghia?

Giuseppe Lanci: Sure. We worked on it in Rome. It's a collaboration between CSC (National School of Cinema of Rome) and Augustus Color. We had a premiere in Bologna and a roundtable which included Tarkovsky's son, Andrei Jr.

What was your intention for the restoration?

At first I was troubled because I knew from the beginning that I wouldn't achieve the same quality of print. Our print was unique: it underwent a special treatment that allowed us to increase contrast and desaturate the image. You can't do that in digital, but we tried really hard to get as close as possible. I worked with Nicola Potera, a great technician. I had to resign myself to this loss of quality compared to the print, but I'm happy with the result––which is the best possible, given the limits of digital.

You previously talked a lot about the work of Giancarlo Barberi.

The printer, yes. He was outstanding. At that time I was working in Bologna, and I remember I picked up Tarkovsky and we drove all the way to Technicolor in Rome. We stayed up until dawn in order to see the first copy printed by Giancarlo and make the corrections.

Can you talk about your choice to use sepia? I know that at first you only discussed color and black-and-white.

We wanted to underline the character's duality between his time in Italy and his life in Russia, so we thought of using color and black-and-white. But when we saw the print in sepia, we found it so interesting that we decided to keep it.

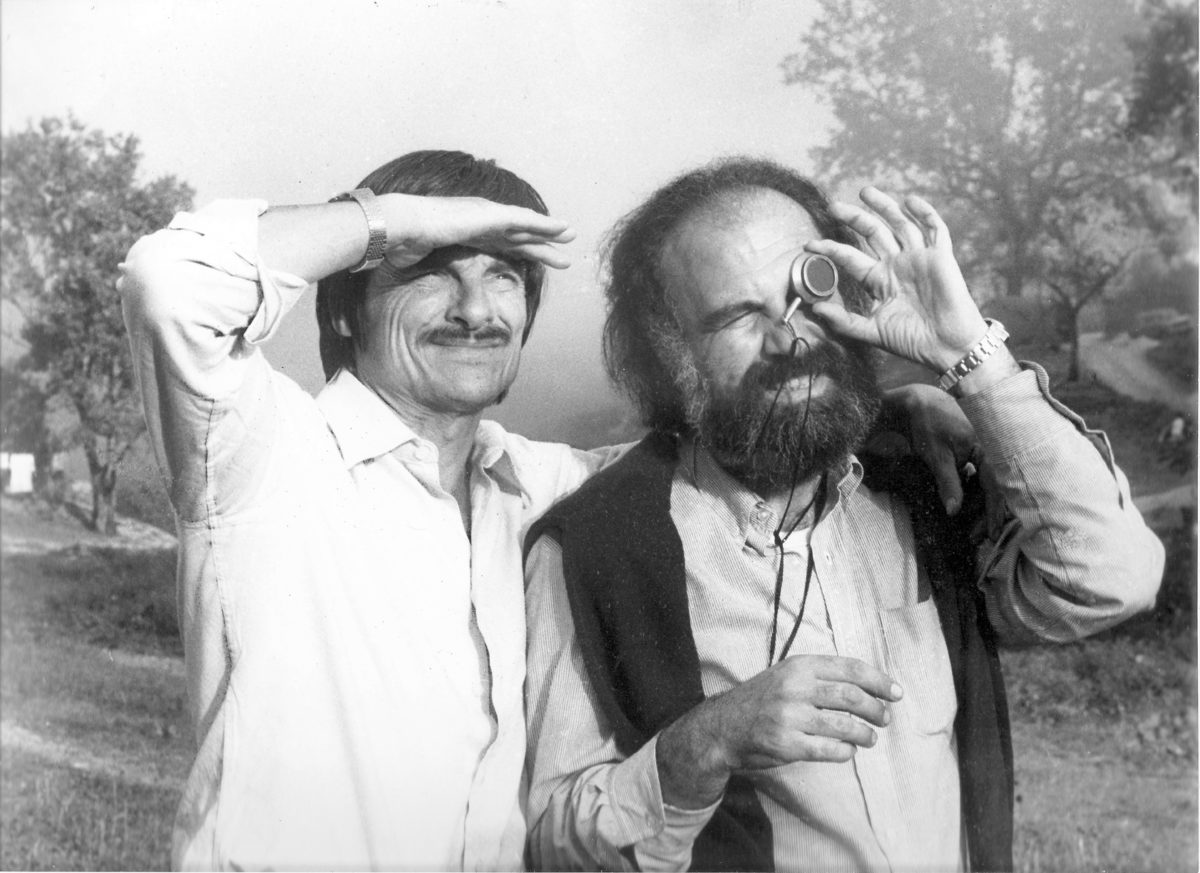

Andrei Tarkovsky and Giuseppe Lanci

What was Tarkovsky's idea for this film? I find it very different from his Russian films. Do you think the collaboration with Tonino Guerra made a big difference?

Tonino Guerra was certainly a big influence, having written the script with him, and let's not forget that part of the film is in Italian and English, so Tarkovsky had to rely on his interpreters. He couldn't completely control the dialogues on set and when it came to dubbing, in the editing process, Tonino Guerra's presence became absolutely necessary.

It feels like watching an Italian film but directed by a Russian director.

All the heads of department and the crew were Italian. I tried very hard to connect with his poetical universe. We talked about the film for several months; then he came back to Italy a second time in the spring of 1982. We started filming at the end of September. I became his shadow and never had any problems when it came to lighting because I had internalized the film. We basically always watched the dailies and he never asked me to make any changes. Later, reading his diaries, I understood that he was very happy with my work.

You said that the light was a narrative tool, but we could also say the meteorological conditions become narrative as well: fog, mist, vapors, even snow in the final scene.

He chose those elements. The fact that we shot in October and November really helped, because there wasn't so much sun. Tarkovsky wanted the fog, which is obviously artificial. If you look at the opening scene, you'll see that the first shot is at dawn and the color of the little black Volkswagen Beetle was intentional so that we could barely see it. Tarkovsky loved the zoom, but this is one of the few scenes where we used faster lenses, keeping the diaphragm at three. As soon as I realized that the light was coming, we started shooting. We shot just one take and I think the result is unique.

That shot really takes you into the atmosphere of the film and adds something to the story. You see, we were supposed to shoot the previous day but it started raining––it was pouring––and when it stopped it was already daylight. We would have completely missed dawn––therefore the atmosphere––and we insisted that it was important not to shoot under those conditions. After many years, I'm still proud of that choice.

That shot is great. Suddenly the camera raises up and we see the church.

Since we couldn't use the zoom, we positioned a crane on top of a dolly on a platform at 15 feet. So at the beginning there's this slight camera movement in order to recreate the effect of the zoom that Tarkovsky liked. And when Jankovskij walks toward the church, the crane moves over the car. So it isn't a pan shot, but a vertical movement of the crane.

That wasn't a real church, right?

No, it was a construction that, from afar, could recall a church. Using the artificial fog, we shot slightly in slow-motion with multiple photograms––32-34 photograms––so that both camera movements and fog movements would look better.

Let's talk about the following scene, when Domiziana Giordano enters the church. It looks as though it must have been very hard to execute. How many days did you need to shoot it?

Two days, I think. When we went for location scouting, we saw a church that wasn't particularly interesting, but then we were told that there was a crypt downstairs. So we went to see it and we felt that it was the right atmosphere for the film. Andrei asked me if I could work under those conditions. The only source of light was a small window, and so I talked with our line producer to see if we could build an external platform in order to have our stage lights there. In the end, that's what we did and we filmed for two days with that as the only light source.

The first blocking is really interesting: Domiziana Giordano is looking at the Madonna del Parto and, as we hear the voice of the priest, the camera moves on him. Did you try it before filming?

No, absolutely. Sometimes Andrei would draw storyboards, but they were more for himself; he wanted to visualize the scene. In this case, we used a transverse dolly for the dialogue between the actress and the priest.

The hotel scene is also very peculiar. The protagonist is in his bedroom and opens the window. It's raining and the camera moves in with a dolly and a zoom. Then there's a change of lighting and the dog enters the room. That's clearly an oneiric moment––the dog is in Russia.

Yes, we saw the dog in a previous flashback. In that scene we used what we called "dynamic light," which is a change of light inside a long take. Initially there's a change because the character turns off the light in the bedroom, then the bathroom, and he opens a window. It's raining and he sits on the bed, and when the light starts changing there's a slow dolly with a zoom-in until we reach a close-up. Meanwhile the light is changing both in the bedroom and in the bathroom, and that's when the dog enters. We are already in another dimension, different from the real one, and that's why the audience accepts the presence of the dog––his entrance from the bathroom and then him lying down next to the protagonist––even though we know that the dog is in Russia. The change of lighting allows the change of dimension.

You have to remember that we didn't have any video control over it because monitors didn't exist at that time, and so we had to trust ourselves and know that when the dolly reached a certain point, we had to turn off a light. I think that is what makes it so special––that there wasn't that a rehearsal mechanism, since it was impossible to establish what to do in a scientific way, I'd say. After the first week, Andrei totally trusted the camera work. I think we took two or three takes, no more, and he chose that one because a piece from the wall outside fell down and that unexpected element gave something more to the scene, and that's why Tarkovsky liked it.

Is the scene where Domiziana Giordano falls on the floor scripted?

[Laughs] Yes, that was scripted. I love wet floors because of the light reflection. And the actress kneels down, like a sprinter in start position, and then runs and falls on the floor on purpose.

Let's talk about the cinematic language of the film. You still teach cinematography at CSC. Once, a friend of mine who also studied there said: "What is Tarkovsky's cinema? A dolly on a door." But that dolly on a door had a spiritual meaning.

[Laughs] Tarkovsky said that the camerawork on Nostalghia had obeyed more to his inner state of anguish than to his rational ideas. The thing is… it has been said in many interviews… Tarkovsky had total control over everything: scenography, costumes. He edited the film himself with two assistants. He chose the music. He worked with the actors until they did exactly what he wanted. Photography was the only thing he couldn't really control until we saw the footage. So he compared our relationship to that of lovers. He said that if during the screening of the dailies he could find what he wanted, then that would be our orgasm. And this is to underline the intimacy that you need to have between directing and photography. Obviously we're talking about print, so you couldn't find out until the screening.

I remember, with great pleasure, the first time we saw the hotel scene––the one with the protagonist and the dog––because it was a risky scene. There were some moments of almost absolute darkness, but those were fundamental to allow the audience to participate in those moments. When it's all lit, there's nothing to discover; you can see everything and there's no interaction at all between audience and film. The viewer is just looking. But if you work with darkness, you force the audience into discovering the film, and that's how you create a connection between those who look at the film and those who make the film. I've seen this film innumerable times obviously––in the printing process, during restorations––and I always choose it for workshops with my students. I have to say that scene always moves me very much.

I think you once said: "The camerawork of Nostalgia is basically perfect, camera movements reach perfection." I'd add: they're also grammatically correct.

Everything depends on which language you choose and what kind of film you want to make. In the case of Tarkovsky, he liked very much transverse and vertical dollies because they wouldn't change the axis of the frame, so what you're doing is trying very hard to keep your horizontal and vertical lines straight. It's a specific directing choice.

As for the flashbacks: when we see the house and his family in Russia with the actors standing and looking at the camera, don't you think those moments recall painting?

In the flashback, the camera looks at his house and his family. It's like a memory which is part of him and so it's like being in his mind––hence the black-and-white or sepia color to give different emotions. This is also why we chose a print that could desaturate the color, in order to have a softer transition between color, black-and-white, and sepia. It was a very intentional choice. We wanted it monochromatic, with few colors, both for the set design and the costumes. The strongest color in the film is Domiziana Giordano's blonde hair.

Did you shoot the scene with the moon in a studio?

No, it's really an exterior. That moon is a big plexiglass with a back installation of lights and a dimmer. It was built on an electrical dolly that would push it vertically. It was built overnight because the first moon we had was plastic and it liquified with the heat. So during the night, a blacksmith built this plexiglass installation for us. You see, there were people who would work all night so that in the morning we could shoot our scene.

It seems to me that Tarkovsky's dollies not only put characters and landscape into dialogue with each other but also position them on the same level of importance. I'm thinking about the scene at Bagno Vignoni at the natural pool, when the camera moves over the actors and keeps going. Something very similar happens when the protagonist is at Domenico's house and then again at the underwater church with the little girl and the poem.

The underwater church was certainly the hardest scene to execute. The first day of shooting was very sunny. You can see the protagonist walking to the church, which is completely white, bathed in sunshine. The next day it was raining––the sky was dark, and inside it was basically nighttime––so I had to invent an artificial light. These are the kind of things that happen, for whatever reason, and make your film better. A more-realistic light probably wouldn't have worked for the meaning of the scene. The artificial light, however––which I created by installing mirrors in the water––works very well because it gives the little girl almost an angelic tone, like that of a vision.

Why do you think we're experiencing a decline in cinematic language today? What is it that you had and we lack?

You rely too much on technology; we were craftsmen. And since the print was expensive and we didn't have any monitor control, we really had to prepare our films, and the director was totally in charge of the camerawork. I was the camera operator in Bertolucci's The Spider's Stratagem, and I can tell you that he would control dolly and crane movements in an almost obsessive way. This means that, as a camera operator, you were just an executor.

Do you think that you were more prepared because you were schooled in Neorealism?

I don't know about that. What I know is that there are two ways of making cinema: on set or in post-production, and I try very hard to teach my students how to make cinema on set, when you're actually shooting. If you don't have an atmosphere for your film, the editor and the director edit with a neutral image. I find that quite absurd.

The 4K restoration of Nostalghia is now playing at Film Forum and will expand.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿