The Last Testament of Frank James

Full transcript of the video below!

Last night, Bob Dylan posted a video to his instagram with a monologue being read out over a still composite image. The monologue presents itself as being "The Last Testament of Frank James". That is, the older brother of notorious outlaw Jesse James. The voice reading out the monologue curiously has a British accent, and delivers it in the way someone reading out an old letter on a history channel documentary might. Some people are suggesting the text was fed into an AI text vocalizer, but I'm not completely convinced of that. This much is true- the source of the text and of the video is a complete mystery.

The image accompanying the video is comprised of the two below:

An 1877 photograph of two men standing outside Jesse James' house:

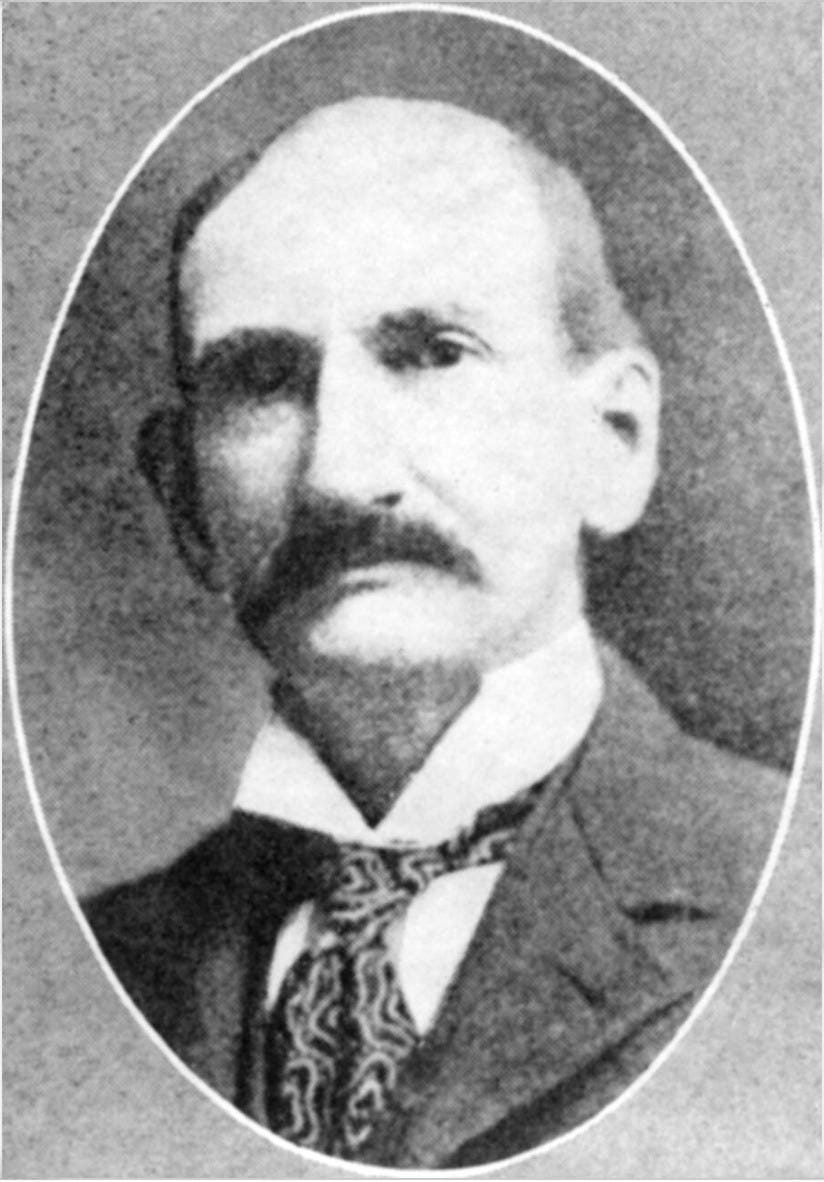

This portrait of Frank James:

This exact version, with the round frame, was sourced from Alamy- something that almost suggests to me that this video WAS created by some sort of educational or historical dramatization resource. The whole thing comes off so much like a piece of museum exhibit or History Channel special; with perhaps the exception of the poetic writing, which some people have pointed out wouldn't sound out of place in Bob's 2003 film, Masked and Anonymous.

If you want to get really dorky with it, the typeface on the image is Fixture Condensed Bold.

Did Bob write it? Is it from some obscure documentary? Did he pull it off a VHS from a 1990s public school classroom? Time will hopefully tell!

Below is a transcript of the entire monologue:

Ladies and gentlemen, I stand before you tonight not as an outlaw, not as a soldier, but as a man who has outlived his time.

I have ridden across the battlefields of the Civil War, the lawless plains of the frontier, and the dusty roads of the outlaw trail.

And now in my old age I have watched the world change around me, until the life I once knew is no more than a tale told in dimly lit parlours.

I was born in 1843 in Clay County, Missouri, on a quiet farm where my father, a Baptist preacher, read scripture by candlelight, and my mother, Zirelda, ruled the house with a will of iron.

Before I could even walk, I was thrown onto a horse's back, and by the time I was old enough to speak, I could ride bareback as fast as the wind through the Missouri hills.

Those were the days of boyhood adventures.

My brother Jesse was four years younger, perhaps you've heard of him.

We spent our summers swimming in the cool, clear waters of the creek near our home, diving from rocks, chasing minnows, and laughing like we had all the time in the world.

But time does not wait, and the world does not care for the dreams of boys.

My father left us for California in the Gold Rush and never returned.

In his place he left behind something that shaped me more than gold ever could.

His books.

Among them were the words of Shakespeare, and I read them like a starving man at a feast.

Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, their words burned into my mind.

And even when I rode in the saddle as a bushwhacker, even when I stood in a courtroom decades later, I could still hear them echoing.

But all the poetry in the world could not stop the storm of war.

You want to hear about the war?

About Quantrill, Bloody Bill Anderson, and the days when we rode with hell on our heels?

You ask me that.

I reckon you better understand.

War ain't like the stories.

It ain't clean, it ain't gallant, and it sure as hell ain't fair.

I was just a boy of 18 when the war came to Missouri, but Missouri had already been a battlefield for years.

Jayhawkers, Union militia, bushwhackers.

We fought neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother.

It was a war with no front lines, no rules, and no mercy.

So I joined Quantrill's Raiders.

Not because I had a choice, but because the war gave me none.

We were ghosts on horseback, striking from the shadows, riding hard, vanishing into the hills before the smoke cleared.

We weren't an army.

We were a vengeance-driven whirlwind, taking back what the Union troops had stolen, giving them the same hell they gave us.

Lawrence, Kansas, 1863.

That's the one folks talk about the most.

We rode in before dawn, 400 men strong, led by Quantrill himself.

The town was full of Unionists, abolitionists, men who had sent their own raiders into Missouri to burn homes and kill our kin.

We hit them like a storm.

Gunfire in the streets, torches lighting up the sky, men falling before they could even grab their weapons.

150 men and boys lay dead before we rode out.

Some called it a massacre.

We called it war.

And then there was Centrelia, 1864.

That wasn't Quantrill's raid, that was Bloody Bill Anderson's.

But I was there.

A train came through, full of Union soldiers on furlough.

We stopped it, dragged them off one by one, and lined them up.

They thought they'd be prisoners.

Instead they were executed, every last one of them.

Some of the boys even scalped the dead.

A message to the Union that Missouri was not theirs.

You might think that was savage, but let me tell you, we were not the only ones who fought that way.

The Union forces killed every guerrilla they caught.

No trials, no mercy.

If you wore the gray, or even if you were just suspected of helping men like us, your house burned, your family suffered, and you were left hanging from a tree.

We didn't fight for generals or battlefields.

We fought for revenge.

We hit Union supply lines, burned down posts, ambushed soldiers in the night.

We were hunted like animals, but the ones hunting us, they feared us more than they feared death itself.

I rode with Quantrill, with Bloody Bill Anderson, with men who didn't expect to live to see the next winter.

Jesse was younger, still green when he joined, but the war hardened him quick.

He learned how to kill, how to strike first, how to never hesitate.

But by 1865 the war was lost.

The South fell, Quantrill was dead, and Missouri?

Missouri was never the same.

We didn't lay down our arms because we suddenly found peace.

We stopped because there was nothing left to fight for.

So you asked me about my exploits?

There were plenty.

Some I'll speak of, some I won't.

War made men out of boys, monsters out of men, and when it was over, well, some of us never stopped riding.

And when the war was done, Jesse and I, we fought on.

For 15 years, Jesse and I, along with Cole Younger and our gang, robbed banks, trains, stagecoaches, and lived by the gun.

We rode the best horses money could buy, stole them when we had to, and could outrun any lawman who dared chase us.

We slept under the stars, in barns, in the homes of men and women who still saw us as Confederate heroes.

And that brings me to something folks often ask me.

Did I survive so long because I was such a good rider?

You ask why I was such a fine rider?

Because I had to be.

I didn't learn to ride in a school or in a cavalry camp.

I learned bareback before I could walk, riding through the hills of Missouri with nothing but my balance and the grip of my knees.

Some folks treat a horse like a tool, I treated mine like a partner.

I knew how far I could push him, how to move with him, how to trust his instincts as much as my own.

Now, as for Jesse, he was fast.

He was fearless.

But he rode like he lived, reckless, daring, sometimes without a second thought for the consequences.

He could outrun most men, but he didn't read a horse the way I did.

He wanted speed, I wanted control.

He was good, no doubt about it.

But was he as good as me?

I don't reckon he'd argue it if he were here.

And do I think I survived because of it?

Absolutely.

There were times the only thing between me and a bullet was the speed of my horse.

I could ride hard when I needed to, but more importantly, I could ride smart.

A good rider doesn't just know how to gallop.

He knows when to slow down, when to weave, when to disappear into the brush and let the posse chase shadows.

I survived because I didn't panic, didn't waste my horse, and didn't let adrenaline do my thinking for me.

Many a man got himself shot because he thought a fast horse would save him.

For the smart horseman?

He knows that the best escape isn't always straight ahead.

It's in the places the Lord don't think to look.

And that's why I'm here, still breathing, long after most of my kind are buried beneath the dust.

But time, you see, has no allegiance to men like us.

The frontier was closing.

The railroads which we had once raided so easily stretched further and further west.

The telegraph sent news faster than any horse could ride.

Lawmen were better organized, better armed, and less afraid.

Then came Northfield, Minnesota, 1876.

We rode in thinking we were unstoppable, but those townsfolk they weren't afraid.

They fought back.

Cole Younger and his brothers were shot to pieces and captured, and Jesse and I.

We ran for our lives, covering nearly 500 miles on foot and horseback before we made it home.

What went wrong at Northfield?

Hell, what didn't?

We had pulled off plenty of jobs before, banks, trains, stagecoaches.

Always outsmarting the law, always staying one step ahead.

But Northfield?

That was different.

That was the one that broke us.

First off, we were too far from home.

We weren't in Missouri or Kentucky where folks might look the other way or even tip their hats to us.

We were in Minnesota, Union country, and we underestimated those people.

See, we thought it'd be like any other town where fear and speed would win the day.

We thought we could ride in, pistols drawn, and be out before anyone knew what hit 'em.

But those folks?

They didn't scare easy.

We split into groups, some of us inside, some outside.

The plan was simple, get in, force the banker to open the safe and get out.

But from the start, things went bad.

The banker, Joseph Lee Haywood, refused to open the vault.

He stood there and told us it was on a time lock, wouldn't budge no matter what we did.

Maybe he was lying, maybe not.

But we threatened him, pistol whipped him, even cut him with a knife.

And still, that man stood his ground.

Meanwhile, out in the street, the whole town figured out what was happening.

Instead of running, they armed themselves.

Storekeepers, blacksmiths, farmers, men who should have had no business standing up to us grabbed their rifles, climbed onto rooftops, and started shooting.

We weren't prepared for a damn war in the middle of the street.

Bullets were flying from every direction, and we couldn't tell where they were coming from.

The boys outside were pinned down, and inside, we had nothing but an empty vault and a dead banker.

That's when we knew we had to get out, fast.

We barely made it to our horses, but even then, it wasn't over.

The town didn't just let us ride away.

They chased us for days.

Possies, bounty hunters, men on horseback hunting us through the woods and prairies.

We lost our way, ran low on food, and before it was all over, the youngers were shot to pieces and captured.

It was the worst damn disaster we ever had.

So what went wrong?

We underestimated those people.

We went in thinking it'd be another easy job, but they fought back, and they fought back hard.

We were used to fear working in our favor, but Northfield didn't fear us, and because of that, the James Younger gang died in Minnesota.

Only Jesse and I made it out, but we never rode with a gang like that again.

After Northfield, the Golden Days were done.

That was the beginning of the end.

Jesse wanted to keep going, keep fighting, but I saw the writing on the wall.

The world was moving on without us.

It was during these years that I found something Jesse never had, peace.

I met a woman named Annie Rolston, the daughter of a wealthy businessman from Independence, Missouri.

She was educated, refined, and strong, a woman who saw more in me than an outlaw.

We married in 1874, and for the first time in my life, I dreamed of something more than running.

Love?

A man like me doesn't get to carry much of that in his saddlebags, not when he spent his life riding from one war to the next.

But yes, there was love.

I loved the land I was born on, the rolling hills of Missouri, the creek where Jesse and I swam as boys, the feel of a horse beneath me and the wide open sky above.

I loved my family, my mother, Zirelda, as tough as they come, who held that house together through war, loss, and the Pinkertons who tried to burn it down.

And Jesse, my brother, who was too wild for the world he lived in, but who I never stopped watching over, even when he wouldn't listen.

And then there was Annie, my wife, the woman who saw something in me beyond the outlaw, beyond the gun.

She came from a different world, educated, refined, everything I wasn't.

But she chose me anyway.

She gave me a home when I was ready to stop running, and a son, Robert Franklin James, who I lived long enough to see grow into a man.

Yes, there was love, but love and an outlaw's life, they don't fit in the same saddle.

I had to put down my guns before I could hold on to the things that mattered, and by the time I did, most of what I had loved was already gone.

So yes, son, there was love, but it was a hard thing to hold on to when you're always looking over your shoulder.

Honor.

Now, there's a word that's been stretched and bent so many ways.

Sometimes wonder if anyone truly knows what it means.

Did I live an honorable life?

Depends on who you ask.

To the Pinkertons, the lawmen, the bankers, I was a thief, a rebel, a scourge that needed to be stamped out.

To the folks who lost money when Jesse and I rode through town, I reckon they'd say I was nothing more than a common criminal.

But honor?

Honor ain't about what the law says, it's about how a man carries himself, how he treats the ones who ride beside him, and whether he can look in the mirror without flinching.

I never killed a man who didn't put himself in the fight first.

I never shot a man in the back.

I never turned on my own.

I kept my word when I gave it, and when I saw the world changing, when I knew the outlaw days were done, I didn't lie to myself.

I stepped away.

I surrendered with my head held high.

Sincere?

I was always sincere.

Whether I was riding with Quantrill, holding up a train, or sitting in a courtroom facing a judge, I never pretended to be something I wasn't.

I didn't try to charm the law into letting me go.

I didn't sell out my brother or my friends to save my own hide.

I didn't hide behind excuses.

So, was I honorable?

I wasn't good in the way folks like to write about in books, but I was true to the life I lived.

And that, I reckon, is the only kind of honor a man like me ever had a chance at.

Regret.

Now, that's a word folks like to throw around.

Do I regret the years I spent as an outlaw?

If I say yes, I'd be a liar.

If I say no, I'd be a fool.

I will tell you this.

A man does what he must to survive the times he's given.

When the war ended, there was no homecoming for men like me.

No warm welcome back into society.

You were hunted, dispossessed, and left with nothing but the guns on our hips.

If we had lain down our arms and begged for mercy, do you think the victors would have shown us any?

No, sir.

The banks we robbed weren't just holding money.

They were holding power.

The kind of power that crushed men like us underfoot.

The railroads weren't just laying track.

They were laying claim to land that didn't belong to them.

So no, I don't regret fighting back.

I don't regret riding fast, shooting straight, or outsmarting the law when the law had already judged me guilty.

But do I regret the hardship?

The blood?

The loss?

Yes.

I regret Jesse dying the way he did, shot in the back in his own home.

I regret my mother losing a son and nearly losing her life at the hands of the Pinkertons.

I regret the youngers spending their best years behind bars while I had the luck to walk free.

And I regret that the world changed faster than we could.

You see, we weren't just running from the law.

We were running from time itself.

And time, time never loses.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿